Looking Back on the Friedman Doctrine

What it was, why it matters and how it's been misunderstood

Hi,

Welcome to Unshared, a newsletter by me, Kyle Edward Williams, about the history of capitalism and the politics of corporate power today. First things first—thanks for subscribing! I’m still early on with this, but my plan is to post every week or every other week things (more or less) related to work on my forthcoming book tentatively titled, Unshared: A Failed History of Corporate Social Responsibility.

And if you haven’t signed up, here’s your chance:

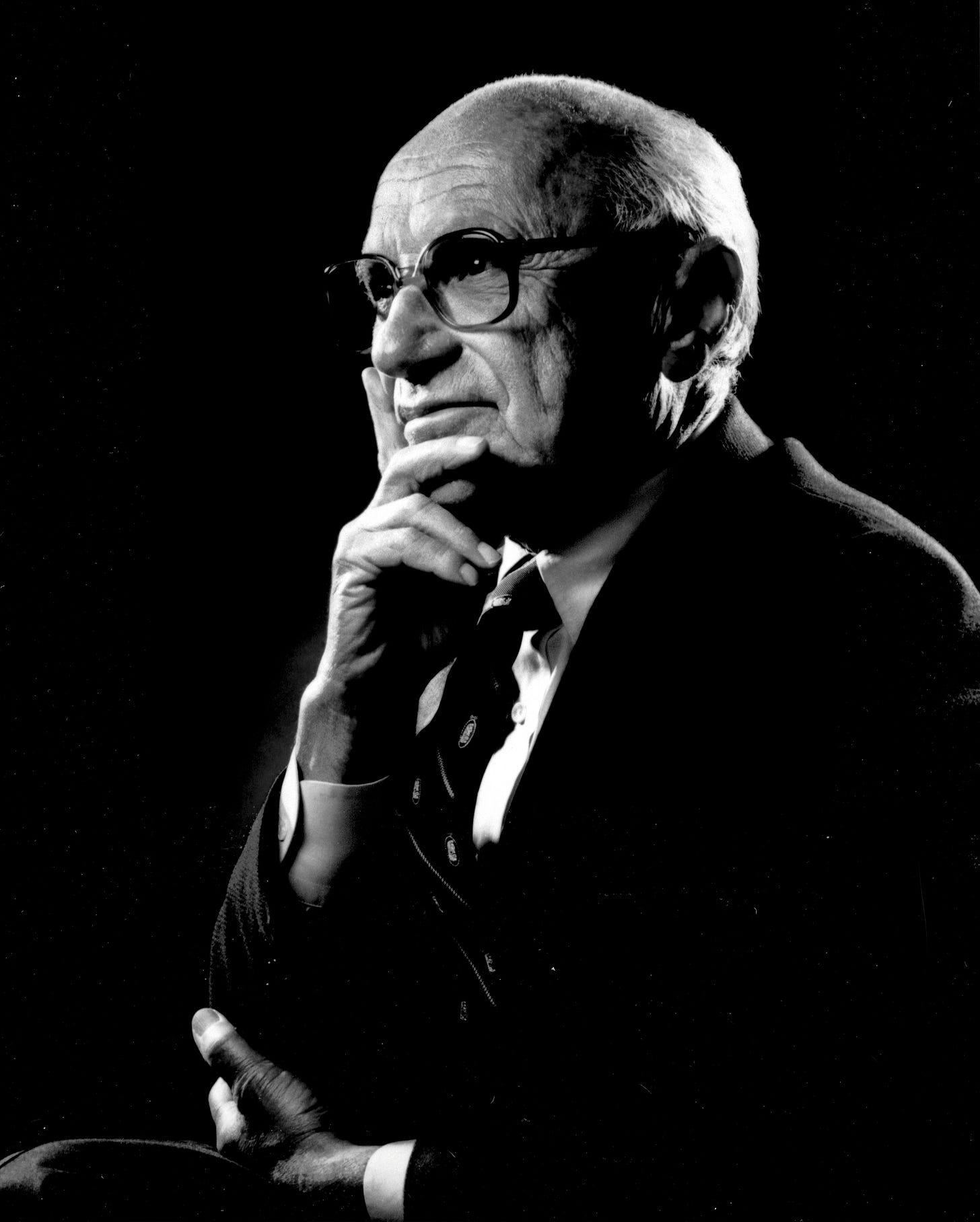

Today I’m going to be writing about an article written by the conservative economist Milton Friedman that was published in the New York Times Magazine 50 years ago this weekend. It was called “A Friedman Doctrine—the Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits” and it made the case that corporate executives should not use the resources of business corporations for social, philanthropic, or charitable purposes. Instead, Friedman offered the persuasive reassurance that seeking profit above all else really is the most responsible and socially beneficial action that business leaders could take.

By 1970, Milton Friedman had achieved a status that nearly all aspiring public intellectuals long for. That is to say, he had influence over public policy at the highest level of government, advising Richard Nixon on the economy (at least until 1971), and he had free reign to comment on the issues of the day in the leading forums of intellectual expression. By the end of the decade, he would be a laureate of the so-called Nobel prize in economics.

The reason he wrote his article for the New York Times Magazine was because a movement of protest had enveloped corporate America over the previous year or so. It started with Black Power activists who demanded concessions from companies like Eastman Kodak over civil rights and employment. Then it spread to anti-Vietnam War and environmental activists. Friedman responded in particular to a group called the Campaign to Make General Motors Responsible, led by Ralph Nader and a small group of young public interest lawyers including Geoffrey Cowan and Philip Moore, who bought GM shares and attended the company’s annual meeting in May 1970. The activists questioned GM’s leadership over racial discrimination, environmental pollution, women’s inclusion, and consumer safety. They even put their own resolutions and candidates for the board of directors to a vote.

Campaign GM failed at the annual shareholders’ meeting—surprise, surprise—but the protest garnered international media attention and put public pressure on the company. General Motors had to do something. And they did: appointing a black man to the board and an environmental expert as a vice president, depositing millions in black-controlled banks, and funding pollution mitigation programs, among other things. By the end of the summer of 1970, they formed a public policy committee to advise the board on social issues. And that was the concession that drew the ire of Milton Friedman. “What does it mean to say that ‘business’ has responsibilities?” he wrote. “Only people can have responsibilities.”

Many retrospectives on the Friedman Doctrine miss this historical context and so they miss the historical point. The article has been treated as the Key to Understanding Everything That Went Wrong With Business. Depending on who you read, it might be the intellectual blueprint for short-termism: the sacrifice of long-term investment for short-term gains through such practices as leveraged stock buybacks. At the very least, it seems like Friedman turned the businessman into little more than a glorified errand boy for Wall Street.

It might also be indicted as the idea that presided over the decline of what the social critic Richard Sennett dubbed “social capitalism.” This was the old American economic regime, which has become so often these days the nostalgic object that politicians promise they will bring back to life. It was many things, but perhaps most basically it was a political economy in which densely-unionized industrial corporations provided long-term employment, benefits, and pensions—and a sense of predictability for ranks of mostly white, male breadwinners.

Did Milton Friedman, of all people, really put an end to that?

The historical significance of the Friedman Doctrine article is so neither so simple nor salacious. For one thing, the big idea that drives Milton Friedman’s reflections on whether corporations have social responsibilities is that the corporation is, in his view, a piece of property owned by the shareholders. Managers can’t and shouldn’t use business resources for social causes or the public good (whatever that means) because the resources at their disposal are the property of the shareholders.

This property theory was the most dominate of all theories of the corporation in the 20th century—and it still is today. After all, its hegemony was established in federal law in the 1930s through a series of New Deal legislative acts—the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935—that became the foundation for the Securities and Exchange Commission regime. For almost 90 years, the SEC has established and enforced fiduciary duties to shareholders for the managers and directors of most major corporations.

In other words, the Friedman Doctrine isn’t nearly as radical as it’s usually made out to be. It may have its own libertarian emphases, but it’s also about as American as apple pie, baseball, and New Deal regulation.

Even if Friedman didn’t always agree with New Deal policymakers (his colleague and fellow libertarian Henry Manne wanted to do away with nearly all securities regulation), he knew the basic ideas he espoused were well founded in American law and politics. With that context, the significance of the Friedman Doctrine becomes clearer. He wasn’t making the case for a radical reconfiguration of American business; he was defending a fairly conservative vision of the status quo against what he feared most: the capitulation of corporate leaders to the new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. For years he had sounded the alarm that liberal-minded businessmen, for all their good intentions about making the world a better place, were introducing what he called in National Review a “subversive doctrine in a free society.” Now, in the face of unprecedented protests, the C-Suite wavered.

By 1975, 60 percent of the largest firms in the country had a high-level committee or executive who directed corporate social responsibility programs focused, for example, on the employment and training of disadvantaged workers or the mitigation of air and water pollution. Over the last fifty years, the majority of large and consumer-facing firms have learned the language of social change and embraced a long and still growing list of causes. Maybe Milton Friedman foresaw all of this when he worried about the possibility of executives capitulating to the “G.M. crusade.” Just as his article was framed in the pages of the New York Times Magazine by photos of Campaign GM activists, anti-pollution protesters, and African-American job trainees, so also corporate social responsibility has historically been flanked by activists and social movements demanding even more substantive concessions than big business is willing to make.

Activists have had lofty goals and organized sophisticated campaigns. Business leaders, too, have indulged in lofty rhetoric matched, sometimes, by good intentions. Both sides can’t escape the rules, however, inscribed in charters of incorporation and federal policy, that determine who gets to make business decisions and how—the rules of corporate governance. And when it comes to the Friedman Doctrine, the rules are on its side.

Even as an activist Wall Street has remade the American and global economy since the 1970s, the corporate social responsibility movement and its various offshoots have thrived. In some ways, you can think of the CSR movement and the shareholder value movement as two sides to the same coin of business history over the last 50 years. But that’s a question for another time.

One or two more things…

If you’re looking for different story about the rise of shareholder value where Friedman and Hayek and the rest of the Chicago School aren’t the main characters, take a look at changes in managerial strategy and theory in the 1960s and early 1970s. There’s a lot more historical work that needs to be done on it, but a good place to start is with Louis Hyman’s Temp. He does a good job of breaking down what was going on at McKinsey & Company and the Boston Consulting Group during those years. A helpful academic article is by Samuel Knafo and Sahil Jai Dutta in the Review of International Political Economy, “The myth of the shareholder revolution and the financialization of the firm.”

My Twitter account is here.

The website is at www.kyleedwardwilliams.com.

As a follow-up to your excellent blog post, check out my paper "The Friedman Doctrine Revisited": https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4770669